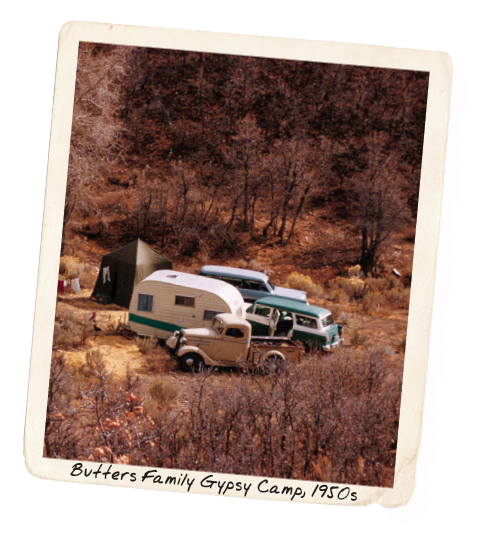

Ask MaryJane Butters about her childhood in Ogden, Utah, and she'll recall camping with her family of seven in the nearby canyons and sagebrush flats, eating baked spuds around the fire and sleeping in a canvas tent. Those were the camping trips that sparked her lifelong love of the backcountry.

“I spent hours just sitting on our front porch looking up at the majestic peaks of the Wasatch Range. I wondered how I could go up there. I didn't know anything about backpacking or camping alone,” MaryJane explained “I just knew I wanted to do it.”

“I spent hours just sitting on our front porch looking up at the majestic peaks of the Wasatch Range. I wondered how I could go up there. I didn't know anything about backpacking or camping alone,” MaryJane explained “I just knew I wanted to do it.”

After graduating from high school in 1971, she tried working as a secretary, but quit to pursue a job that would take her to the high country. By the next summer, she was there, watching for fires from a mountaintop lookout tower outside of Weippe, Idaho.

“That summer I read everything Henry David Thoreau ever wrote. I got real dreamy, with a desire to live simply, with a love of living in just the silence of the forest. I never wanted to leave.”

When the summertime job ended, she enrolled in the forestry program at Utah State University. College opened up a world of new ideas that filled her winter, just as the lessons of the mountains enveloped her in summer.

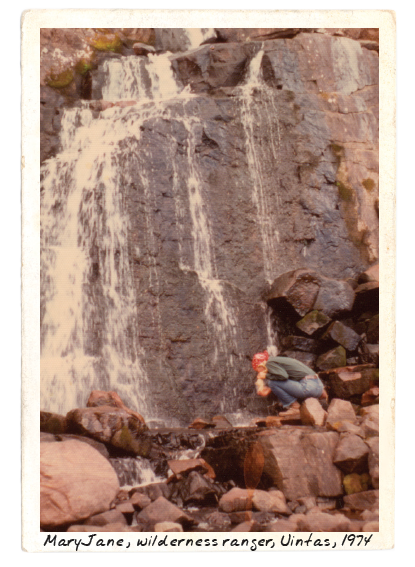

In 1973, she went back to the Idaho mountains and then returned to college in Utah. The cycle was not repeated because, during the spring of 1974, she saw an advertisement that changed her life. The United States Forest Service sought women for wilderness ranger positions. The challenge appealed to her pioneering spirit and her love of the backcountry.

“They hired three women that year. We were the first women wilderness rangers in the U.S. I spent the next two summers in the Uinta Mountains of northern Utah, maintaining trails and cleaning up old sheepherder camps, ten days in and four days out. I often spent five or more days without seeing anyone. I fished and explored. It was heaven.”

After her first summer as a ranger, she returned to college, but realized that she needed to keep working with her hands. In the middle of art history class, she walked out and never returned.

She drove to Ogden and enrolled at a vocational school to learn carpentry. Later that winter, with a certificate of carpentry proficiency in hand, she was hired to build houses at the nearby Hill Air Force Base--the only woman on the crew.

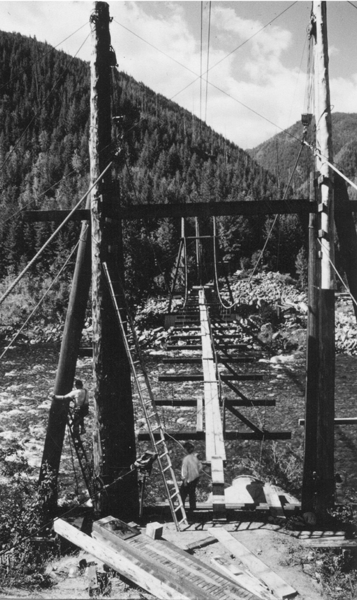

Early in 1976, she landed the job of her dreams: a return to the wilderness, as the first woman station guard at the Moose Creek Ranger Station, the most remote Forest Service district in the continental U.S., 25 miles from the nearest road, in Idaho's Selway-Bitterroot Wilderness Area. Her new husband, John McCarthy, was invited to come along as a trail crew volunteer.

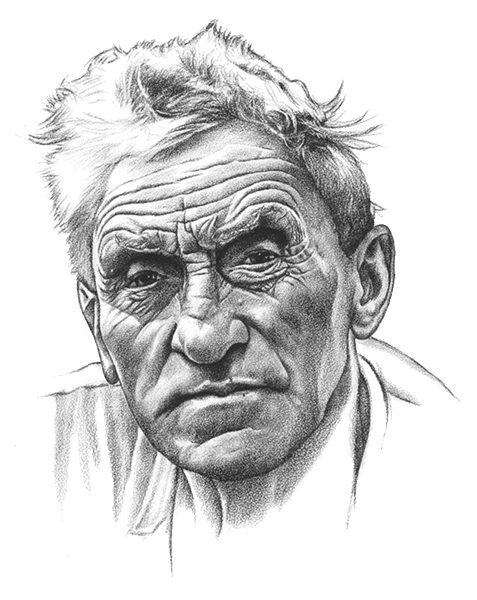

Flying into Moose Creek in a little Cessna for the first time in April of 1976, she met the man whose skills and spirit had already made him a legend in the Forest Service: Emil Keck. Keck, a former gyppo logger and self-taught woodsman, had been hired as a fire control officer and construction crew chief at the wilderness station in 1962. He lived at the station year-round. His ability to cut trails and build bridges with nothing but hand tools was universally respected, and his ability to inspire and instruct young workers in the values of the wilderness created legions of devoted disciples.

MaryJane's first encounter with him was classic Emil in all his gruffness.

“As I walked in, Emil told me to turn around and walk back out. He didn't like the idea of a woman working there. Then he saw the tool chest I was carrying. He asked me if I made it, and when I said yes, he said: 'OK, then you can stay.'“

“Emil became my life's mentor. He taught me how to work hard, and how to make work my life. He was a genius at making things. He was well-read, tenacious, curious, and real intense. He had no time for bureaucracy. One time, the bureaucrats sent him a gas-powered lawnmower, because some VIP's were coming to Moose Creek and they wanted the grass tidy. He just took the lawnmower out into the woods and dug a big hole and buried it. When they arrived, and the grass was not mowed, he just told them he buried their damn machine and dared them to do anything about it.”

MaryJane still has a misty smile when she talks about Emil.”He called me Buttercup, and he told me I was the best station guard he'd seen since 1962. But I had to leave after two years. My biological clock was ticking loudly. I told him I was going to live on a farm and have a son and name him Emil.”

|

|

Emil Keck

|

“As I was leaving, he told me that he'd give me the shirt off his back--and then he did. He stripped off his shirt and gave it to me. I still have that shirt, with all its meticulous patches, in a plastic bag at home. It still smells like Emil.”

Leaving Moose Creek, MaryJane and John became ranch hands on the 30,000 acre Hitchcock Ranch in Idaho's rugged Hells Canyon region. Their daughter, Megan, was born in 1979, and four years later, on Emil Keck's birthday, October 20, their son was born. He is also named Emil.

Emil Keck met his namesake several times. Unfortunately, Keck was fired by the U.S Forest Service, forced to leave Moose Creek, and died of a broken heart a year later, in 1990, at age 77.

The work of raising two children, remodeling a succession of old houses, enjoying backcountry hikes, and growing gardens full of food filled the next few years. Throughout that time, MaryJane never forgot her dream of a small family farm.

“I envisioned an old farm in northern Idaho hidden at the end of a dirt road. I dreamed of chicken coops, barns, root cellars, fruit trees in bloom, clematis vines, lilacs, wild roses, irises, and gardens. Then in 1986, I saw an ad in a newspaper for a five-acre homestead. It sounded perfect, so I called and bought it almost sight-unseen. I had most of the money we needed stashed in an old coffee can. It was an old relic of a house, without any plumbing, but I knew it was my dream place. I named it Paradise Farm, since it was hidden at the base of Paradise Ridge, 8 miles from Moscow, Idaho.”

“Before our arrival, two bachelor brothers had been born, lived, and died here. They were suspended in time. I loved the 'step back in time' feel of Paradise Farm, with its old outbuildings and turn of the century farmhouse.”

Her world seemed idyllic, but changes were coming. John left as their marriage ended in divorce, and then in May of 1986, the Pacific Northwest was dosed with releases from the nuclear accident at Chernobyl.

“I got mad. Motherhood brought out a special activism in me.”

MaryJane called a public meeting to discuss the threat of nuclear radiation exposure, specifically from the Hanford nuclear facility in nearby eastern Washington. Thirty people showed up at the meeting. They named their new organization Palouse-Clearwater Hanford Watch, and elected MaryJane as president.

Hanford Watch was one of several anti-nuclear groups formed in the Pacific Northwest after the Chernobyl accident. The group was energetic, resourceful and effective. They focused public interest on the dangers of continued nuclear activity at Hanford, and ultimately shut down the nuclear reactor there that was identical in design to the Chernobyl facility.

“It was an intoxicating era, so exciting. We moved beyond the Hanford issue to form a non-profit environmental group we called the Palouse-Clearwater Environmental Institute. We got involved in lots of water quality, transportation and agricultural issues--like the attack of the Russian wheat aphids.”

In 1989, to counter the growing number of aphids in the region, agricultural officials were suggesting the wholesale spraying of pesticides that had been implicated in human health problems. MaryJane called a public meeting to discuss the dangers. In 1989, to counter the growing number of aphids in the region, agricultural officials were suggesting the wholesale spraying of pesticides that had been implicated in human health problems. MaryJane called a public meeting to discuss the dangers.

“At that meeting, I remember getting knots in my stomach. It was so divisive. I just did not want to try to make progress by confronting people like that. I did not see that we were changing the hearts of people. I knew I would have to stop.”

At the same meeting, MaryJane met a farmer who grew a small hard-skinned garbanzo bean known as the “desi“ variety. The desi beans were unusual since the plants repelled insects and needed no pesticide applications to grow well in the region. However, the desi beans were also of little agricultural value, since there was no established market for them.

“I was interested in this farmer's story. I decided to reach across to the farmer. I bought some of those desi beans. I wanted to design a product that would create a market for that bean. I took the beans home and ground them into a coarse meal using my electric drill attached to my home grain grinder.”

“I experimented with creating falafel, a mid-eastern staple, but relatively unknown food in this country at that time. I ground the beans, tried different spices, and fed it to my kids. They liked it, but we joked that we were always eating 'Mom's awful falafel.' By 1990, I started marketing it locally under the Paradise Farm label.”

MaryJane resigned as president of the Palouse-Clearwater Environmental Institute to focus on building a market for these under-utilized agricultural crops. PCEI has remained a vital environmental organization in the Moscow area, with five staff and dozens of volunteers who work on a broad range of issues.

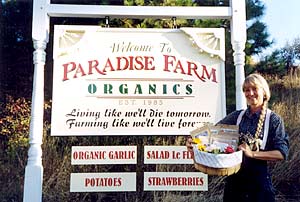

In 1993, her business was incorporated as Paradise Farm Organics, Inc. A private stock offering provided the funding needed to expand, and to recover from the disastrous effects of a fire that consumed the old farmhouse and production facility at Paradise Farm.

|

|

(c) National Geographic, December 1995, Jim Richardson

|

“I became interested in working with other farmers. I realized that if I have a gripe with the way farmers are doing their business, I could create a market for a product and then go to the farmer and tell them that if they grow X number of pounds according to these standards, I will buy them.”

“If I want the farmers here to grow organic, I need to help them make that transition.”

Experimenting, MaryJane ultimately created more than 50 ready-to-eat dried foods using organic ingredients.

Her business has flourished, doubling in sales annually and benefiting from a successful public stock offering in 1999 that raised half of a million dollars for expansion and website construction.

During the same time, MaryJane found a partner to share both her business and her life.

“Over the years as I lived here at Paradise Farm, I occasionally caught the brilliant smile and helping hand of my neighbor, Nick Ogle. Nick's 600-acre farm borders mine on two sides. He was born into farming and started driving tractors and working with his father when he was ten years old. He and his parents still work the ground Nick grew up on. Nick loves flowers. The Paradise Ridge wildflower bouquets he brings me are no longer anonymously left upon my doorstep. In 1993, Nick became my husband.”

MaryJane is the company's president, and Nick is in charge of the production facilities. And together they direct the growing of organic herbs, produce and grains at their farm.

Their union was immortalized in the National Geographic magazine by a writer and a photographer who visited Paradise Farm for an article on organic agriculture. The photograph of MaryJane and Nick fills page 89 of the December 1995 issue. The article focuses on their successful marketing of a new kind of convenience food: organic meals for backpackers, rafters, kayakers and other outdoor enthusiasts.

The easy-to-prepare, tasty, and organic foods she has created are what she dreamed of eating decades earlier when she first started living in the backcountry.

“I eat this food at home, and I eat this food after hiking all day. This is the real food that I wanted to have years ago. Here, at last, is your organic alternative to industrial-grade backpacking foods.”

– by Bill London

June 10, 2002

|